Do the Inner Workings of the Design Industry Match the Beauty Everyone Sees?

Beneath the sleek surfaces of the design industry — architecture, interior design and luxury furniture design — lies a sector in turmoil. From controversial stories about architecture’s unpaid labour crisis and interior design’s role in the housing shortage to greenwashing in hospitality, the industry faces a profound reckoning. LUXUO uncovers the unsavoury issues and symptoms of a deeper conflict between aesthetics and ethics.

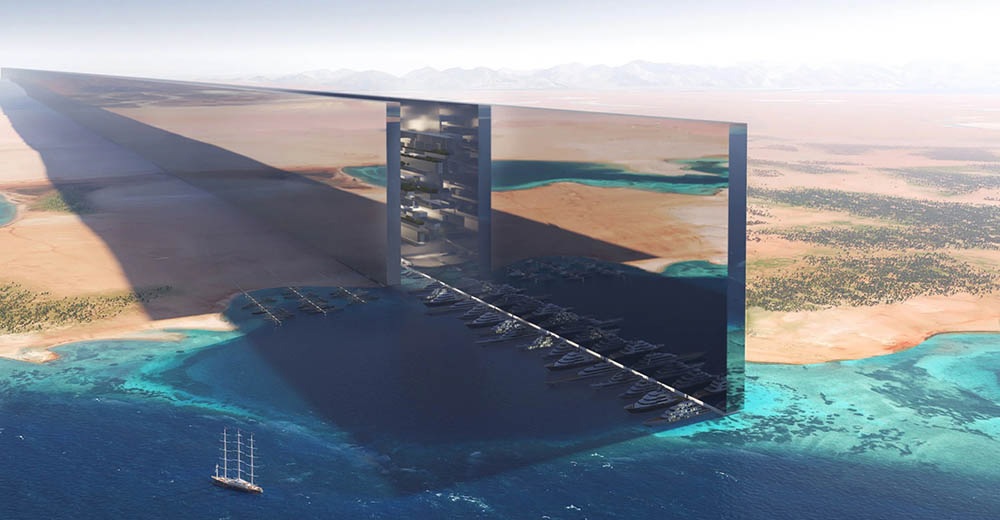

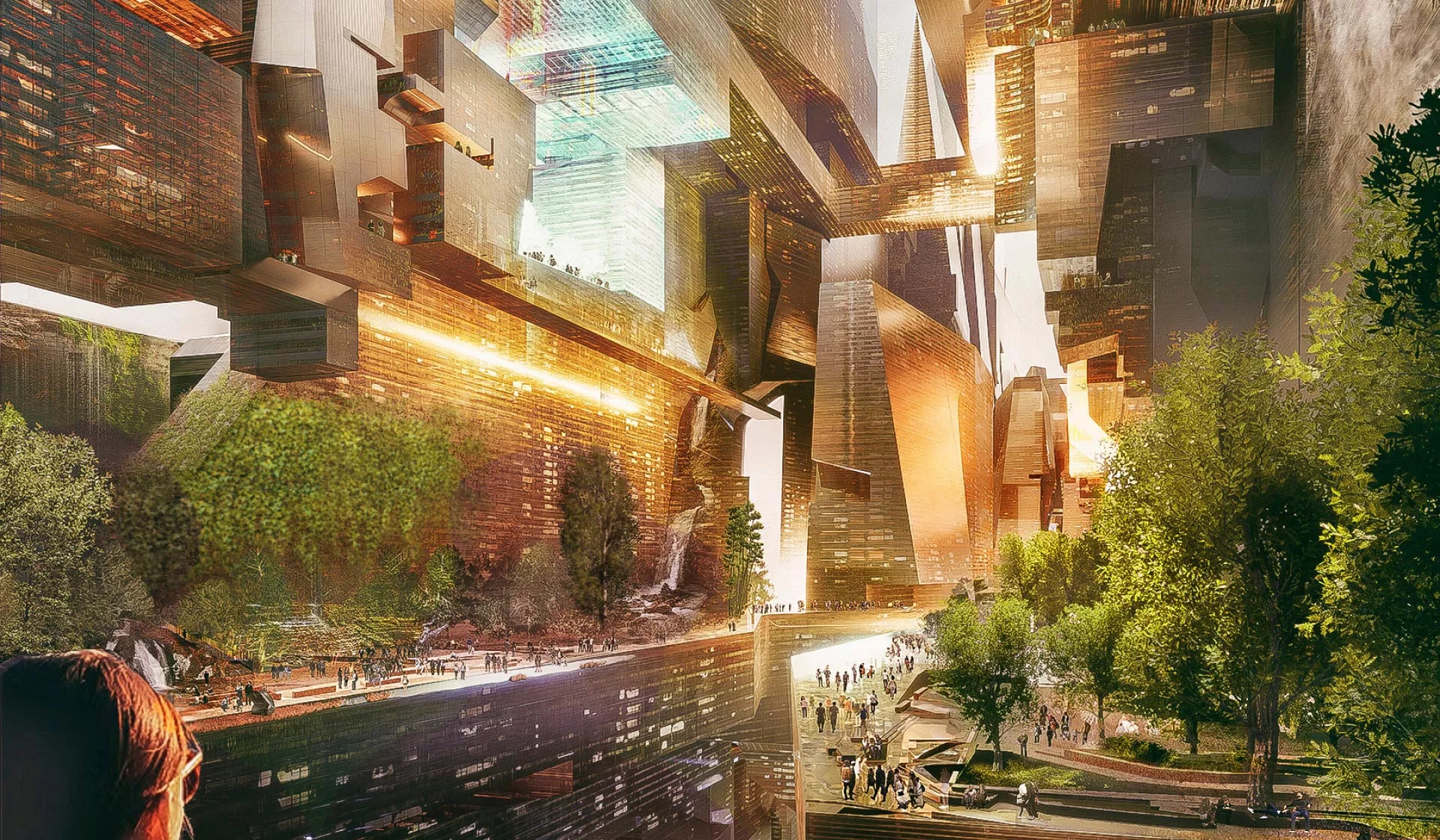

The Reality Check of Saudi Arabia’s “The Line”

With its flagship project, The Line — positioned as a ground-breaking model for urban living — Saudi Arabia’s USD 500 billion NEOM megaproject was meant to be the pinnacle of futuristic ambition. It promised a car-free, AI-run nirvana for nine million people and was marketed as a 170-km-long, mirrored linear city spanning the desert. The initiative, however, is being substantially cut back, as confirmed by The Guardian’s research. Industry analysts interpret this as a scathing acknowledgement of profound failure rather than a simple recalibration. The Line’s controversy is no longer a side issue; rather, it serves as a prime example of how architectural excess, environmental carelessness and human rights violations can sabotage even the most lavishly funded plans.

Critics who have long lamented The Line as an architectural dystopia are vindicated by the cutting back from a commercial and design standpoint. Urban planners criticised the idea of a 500-metre-tall, massive wall slicing through the desert as a throwback to an outdated, authoritarian design paradigm. In favour of a sterile, AI-managed world that prioritises a single aesthetic over human-scale living and community, it rejects centuries of organic urban evolution. The deadly gap between idealistic rhetoric and practical reality is revealed by the reported reduction of its original demographic targets and physical footprint by 2024. According to the international architectural community, this is not innovation; rather, it is an authoritarian dream that disregards the introductory sociology and economics of how prosperous cities truly operate.

Additionally, the project’s alleged sustainability credentials have proven to be a risky front. The environmental rage is grounded in real, catastrophic risks rather than just idealistic sentiment. In one of the driest places on Earth, building a city of this size within a fragile desert ecosystem requires an unprecedented amount of energy and water. When millions of tons of glass and concrete are produced, the initial carbon footprint is so large that it negates the promise of using renewable energy in the future.

The Line’s most permanent stain is, above all, the human cost. A lengthy, gloomy shadow is cast over the project’s glossy representations by the Huwaitat tribe’s forcible relocation and the alleged persecution of those who resisted, including reports of arrests and death sentences. This is a fundamental wrong — not just a contentious — issue. Watching this initiative develop has led to the sobering realisation for some that ecological neglect and forceful evictions cannot serve as the foundation for real progress. The Line is a sobering reminder that ambition and concrete should never come before people and conscience in the sake of legacy. The world is now recognising that it is a mirage.

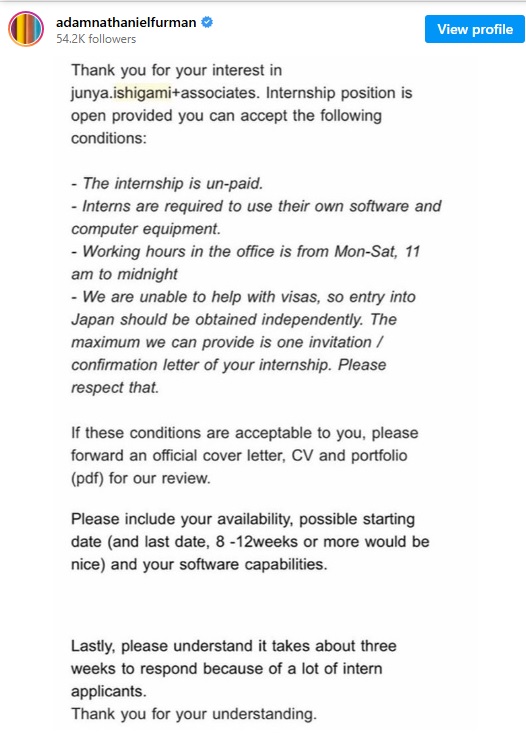

The Unpaid Labour Backlash: Architecture’s Reckoning with Exploitative Internships

Junya Ishigami faced the ire of the architecture industry for unpaid internships. Image: Archiproducts. (left) and An IG post about Junya Ishigami’s unpaid internships. Image: adamnathanielfurman. (right)

The systemic reliance on unpaid internships is the filthy secret that the architecture profession has long been avoiding. The disclosure that the 2019 Serpentine Pavilion’s design firm — Junya Ishigami + Associates — had used unpaid interns sparked a recent uproar, compelling a critical analysis of the exploitative practices within the industry (Dezeen, 2019). This presents a fundamental ethical and equitable challenge, exposing a corporate model based on insecure labour that disadvantages everyone except the most affluent newcomers.

The uproar — vocally led by advocacy groups like The Architecture Lobby — rightly frames unpaid work as an existential threat to the field’s diversity and integrity. As they stated, these practices “exploit aspiring architects and contribute to the profession’s lack of socioeconomic diversity” (Archinect, 2019). The message is clear: when only those who can afford to work for free can enter the profession, architecture becomes an echo chamber of privilege, stifling innovation and relevance.

In response, the tide is formally turning. The National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) has now firmly reaffirmed its opposition to unpaid internships, a significant move that empowers interns and validates their worth (Archpaper, 2021). This institutional shift — pressured by relentless advocacy — marks a pivotal step toward reform. The path forward demands more than statements; it requires a fundamental recalibration of firm economics to ensure fair compensation. The industry is finally being forced to build a more equitable foundation, one paid intern at a time. This is a crucial step in attracting and retaining the diverse talent necessary for the profession to truly evolve and meet future challenges, ensuring its very survival.

The uproar is being loudly led by advocacy groups such as The Architecture Lobby, which accurately paints unpaid labour as an existential threat to the sector’s variety and quality. According to them, these practices “take advantage of aspiring architects and contribute to the lack of socioeconomic diversity in the profession” (Archinect, 2019). The message is clear: when only those who can afford to work for free may enter the field, architecture becomes an echo chamber of privilege that stifles innovation and relevance.

A Design Dynasty Divided: Cassina and Molteni & C’s Battle for Ponti’s Throne

Heritage brands Cassina and Molteni & C were involved in a high-stakes court battle over the legacy of maestro Gio Ponti in a spectacular clash of Italian design titans. The re-edition of Ponti’s famous “chairs 819” and “chairs 836” lounge chairs was the source of the disagreement; both businesses asserted legitimate ownership of the mid-century designs.

According to Dezeen, the dispute reached its peak in 2017 during Milan Design Week, when both companies unveiled their interpretations of the classic items. Directly collaborating with Ponti’s heirs, Molteni & C obtained a preliminary injunction against Cassina, the company that had produced the chairs in the 1950s. The court decided in Molteni’s favour, upholding that the Ponti estate — not the original manufacturer — had copyright protection that lasted for 70 years after the author’s passing.

This court ruling highlighted that authorial rights go beyond previous manufacturing agreements and set a significant precedent in design copyright. The decision served as a powerful reminder to the luxury furniture industry that — in the conflict between authorship and legacy — the creator’s legacy ultimately prevails. In a market that is becoming increasingly competitive and legally complex, the decision has significantly altered how design firms handle intellectual property agreements and historical revivals, requiring brands to carefully obtain estate authorisation before resurrecting past designs.

An Inconvenient Truth: Interior Design’s Long-Overdue Reckoning with Racism

The interior design sector — which has long been seen as a stronghold of apolitical aesthetics — must tackle its deeply ingrained racial biases. British Vogue revealed that this is a structural crisis of exclusion, cultural appropriation and a colonial past that has consistently favoured whiteness as the default norm of elegance and beauty rather than an issue of overt prejudice.

A glaring lack of diversity was evident in the debate, which was further highlighted by the 2020 Black Lives Matter campaign. Just 2 percent of members of the American Society of Interior Designers in the US identified as Black, a figure similar to that of the UK industry where BIPOC voices in prominent editorial positions and firms remain glaringly uncommon — whose taste is deemed acceptable and whose is disregarded is determined by this systemic exclusion.

With phrases like “tribal” and “ethnic” being used as catch-alls for non-Western designs, depriving them of cultural context and significance, the industry’s terminology itself turned into a battlefield. Moreover, Eurocentric values — neutral colour schemes, minimalism — are frequently presented as intrinsically better, subtly portraying the rich customs of Asian, Latin American and African civilisations as “other.” Because of its colonial origins, this aesthetic hierarchy reinforces a harmful bias.

The Aesthetic Divide: Interior Design’s Complicity in the Housing Crisis

The interior design business is embroiled in a growing debate that goes right to its core: its obsession with luxury and its involvement in escalating social injustice. The main criticism is of “aesthetic gentrification,” in which the streamlined, minimalist ideas promoted by design media are used as a model for urban growth. According to academic research on social justice, this homogenised style frequently serves as an excuse to deprive neighbourhoods of their genuine — albeit faded — individuality, rendering them expensive for long-term, lower-income residents.

This trend directly exacerbates the housing issue. Essential resources and political will are diverted from the pressing need for high-quality, affordable social housing by the industry’s focus on high-profit, luxury developments for the wealthy. Debates over “good taste” are a significant privilege for people struggling to find council homes or decent rental properties. Insecurity and the possibility of homelessness — problems that the design community has mostly overlooked — define their experience.

The dispute necessitates an examination. The industry must go beyond token diversity programs to achieve true social fairness. It must aggressively push for legislative changes, prioritise community-led initiatives over corporate interests and utilise its creativity to develop respectable and reasonably priced housing options. Making sure everyone has a secure place to live is where the most pertinent design justice can be found, not in a showroom.

The Green Veneer: Hospitality Design’s Greenwashing Problem

Due to extensive greenwashing, the premium hospitality design business is experiencing a crisis of legitimacy. Many “design hotels” are criticised for prioritising aesthetically pleasing eco-features over a truly sustainable model, creating a dangerous divergence between perception and reality — even as they promote living walls and reclaimed timber.

The “boutique sustainability” conundrum is a key point of contention. Hotels promote hyper-local materials, but their operations are outweighed by the carbon-intensive travel emissions of their international customers. This selective reporting produces a false sense of accountability.

Additionally, the industry’s need for custom, trendy interiors runs counter to the ideas of the circular economy. During renovations, highly specialised designs are routinely disposed of in landfills, producing a significant amount of garbage. Critics also point to a breakdown in social sustainability, where an emphasis on visually appealing regional crafts can conceal subpar labour standards and demonstrate a lack of knowledge about a comprehensive ethical framework.

Notably, the industry ignores embodied carbon. According to 2023 research by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, the building industry is responsible for 37 percent of worldwide energy-related emissions, with 10 percent coming from the actual construction process. Before a hotel even opens, a significant carbon footprint is left by the preference for new construction versus adaptive reuse. The industry’s sustainability claims will remain highly contentious until these structural problems are addressed, rather than merely making token gestures.

For more design reads, click here.

The post Do the Inner Workings of the Design Industry Match the Beauty Everyone Sees? appeared first on LUXUO.