From Steel to Ceramic: How Material Mastery Shapes The Future of Luxury Watchmaking

One cannot understand watchmaking today without a firm grasp on history, and reality too. It is all too easy to go along with watchmaking brands when they brandish carbon fibre cases as if they are the very latest thing. As it happens, this spoils the fact that carbon fibre remains absurdly useful in watchmaking by virtue of its extremely high specific strength rating (see the sidebar below). More than anything though, empty marketing talk simply ruins the realization that there might be only two Swiss brands making ceramic cases in sand or dessert yellow.

In other words, innovation is not so much the story as rarity is – for the purposes of this extended story then, we will be relegating the very idea of innovation to the sidelines. Now, if you are longtime reader, you might find this odd but bear with us as we meander through yet another of our materials specials. And, for those of you who wonder about the ceramic cases, we might get to an answer, but the idea there is for you to have some fun figuring things out.

As we wrote last year, one of our first deep dives into the materials that make up the watches that we love was in 2016. It was not a regular feature of the magazine until 2019 though, when it anchored the Summer issue. Issue #53 featured the now-discontinued TAG Heuer Autovia Isograph (with the word Isograph on the dial) in bronze and, with this ambiguous start, we were off to the races. The materials special has appeared in every Summer issue since, making this the seventh instalment in an unbroken row. This, of course, is also a bit of history and directly informs the story this issue.

Read More: New Balance – TAG Heuer Autavia Isograph

While we have managed to cover every typical (and some very atypical) material used by the watchmaking trade, some context is useful before we start over. Yes, we are going over everything again without properly covering steel, sort of. The alloy gets its due right here, as part of this recap or rethread, as you please. Steel is by far the most common and popular material in watchmaking, fine or otherwise, rivalled only by brass and plastic.

Watches cased in steel represent more than 50% of all watches exported from Switzerland, as of 2024 and this has remained relatively consistent over the last 10 years (source: Federation of Swiss Watchmaking otherwise known as the FH. Most figures cited in this segment are from the FH or Statista, where noted). An entire materials special dedicated to steel seemed a bit much, given that there is nothing new to report on it and it has not gotten itself on the rare and unusual materials list.

Narrative Purpose

We should pause here to note that all figures from the FH represent Swiss exports at export prices, not retail prices. These are also not indicative of watches from other countries of origin nor of currencies other than the Swiss franc. The FH figures also do not include the Swiss domestic market, which also includes what tourists buy in-country.

In any event, the trio of steel, brass and plastic is in everything, from the inside out, from cases to movements and beyond. For the sake of a more complete picture, we do include steel in this story, although it gets far less space than any other material, relative to the specials that each material once received.

But steel has a narrative purpose here, an appropriate one as it happens. In this very issue, the ever-popular Tick Talk (formerly known as The Conversation) also sees the editors grapple with the issue of how watches in gold and platinum are priced.

Read More: The Conversation: Engineering Success

This is vital to grasp because precious metals have been the lifeblood of the watch trade, even as Swiss export volumes have tumbled. The industry is down 5.8 percent, year-on-year (to end of March, when this story was written). This follows a slump of 9.4 percent last year. Over the past decade, total volumes have almost halved, decreasing from 28.1 million units in 2015 to 15.3 million last year. By way of contrast, value has proved consistent, so watch brands have been doing the same business with fewer watches. This is down to the ability of brands to charge a premium on gold and platinum, and steel too, to an extent.

The volume reality also contrasts strongly with sentiments expressed by the leaders of the watch business since 2021. To cite just one example, Breitling CEO Georges Kern told EuropaStar in 2023 that he expected the brand to surpass CHF1 billion that year. According to the latest Morgan Stanley estimates (published this year, for 2024), the brand hit CHF850 million, which is down from the CHF870 million estimated for 2023. For the record, we use this example to highlight the lack of useful reference numbers in watchmaking. Breitling itself estimates that its production is somewhere between 250,000-280,000 units in 2023 but Morgan Stanley only lists 178,000 units sold in 2023 and 160,000 units in 2024. Those are no small discrepancies, to be mild about it, and Breitling is not an outlier nor a special case.

Logical Extrapolations

Our solution to the issue of non-transparency in Swiss watchmaking is to make logical extrapolations and guess-timates. It is not great but it is the best anyone can do, and also explains why we are citing the Morgan Stanley figures. The industry might criticize this report but it does little to make the job of third-party reporting easier.

To caveat the above point about guess-timation though, there are serious limitations. For example, one might think that the Daytona model is of minor importance to Rolex, just going by its lonely place in the catalogue as the brand’s only chronograph. According to the brand’s website, there are 47 models in the current catalogue, which pales when compared with Omega’s 114 models, just in the Speedmaster family; there are also chronographs in the Seamaster range, to cite just one other Omega collection. A search for ‘chronograph’ on the Breitling website turns up 123 watches.So, one could conclude that the chronograph is somewhat less important to Rolex than it is to either Omega or Breitling.

Read More: Rolex 24 at Daytona 2025 Pushes Limits of Man and Machine

Obviously, the conclusion above is wrong and there is just not enough information to make any sort of judgment or comparison – at least not with just the above-mentioned publicly available data. Even if the chronograph is, in fact, less important to Rolex than to other brands, the guesswork we employed is just wrong. This serves to illustrate the dangers of guesswork when the scarcity of facts renders good answers unavailable. This story will see us avoid rank speculation and avoid tempting logical fallacies, or at least we shall endeavour to make it so. When good data points are unavailable, we might make some leaps but we will signpost these where possible.

Still Loving You

Steel and gold also frame this opener because both are deeply connected with watchmaking, with silver having fallen by the wayside in contemporary times. We posit that a key moment was the 1972 debut of the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak, which actually appeared in a white gold case as a prototype at Baselworld; the casemaker had yet to develop the means to create the same in steel. Yes, like it or not, the ripples created by this seminal watch are still being felt. The particular ripple that concerns us here is the decision by the Le Brassus watchmaker to offer fine finishing for the steel case, as if it was gold. Patek Philippe sealed the deal for the broader collecting world with the thematically similar Nautilus in 1976. Treating steel as something precious must have seemed mad, but it gave watchmakers the ability to charge gold prices – more even – while giving collectors reason to feel that the watches were something above anything in gold or steel.

Read More: An Azure Evolution of Patek Philippe’s Ladies’ Nautilus 7010/1G-013

Needless to say, an entire crop of watches emerged (in part) to test this proposition, where a metal that was once merely functional (or good enough for the hoi polloi) was transformed and elevated to the noble ranks of its precious brethren. Effectively, this rise in status happened because the watchmakers said so. From here, we can trace a through line that results eventually in the rise of Hublot and Richard Mille – the latter is especially famous for its Midas touch, giving technically exciting materials an appeal far higher than anything merely precious. Yes, “merely,” although all brands that raised the game for steel and other prosaic materials also gained the chance to skew prices higher on the precious metal variants they inevitably introduced.

Now, arguments about the above subject have gripped the collector community since before that Scorpions tune was an earworm, online and offline. The fact remains that Richard Mille exists and continues to ply its trade successfully. Whatever watchmaker can pull this trick off again will offer a lifeline to the entire industry. This is the key point of this tale, and we will be returning to it repeatedly. In this broadly ambitious section, we propose that such a move will happen not with Alusic (pair with Richard Mille and Google) but ceramic or titanium. Probably both. Basically, something that watchmakers are already using, just without the razzle-dazzle of a transformative campaign.

As Rare As Dust

In a nutshell, as mentioned, transformation is the point and the very heart of this narrative. We danced around this subject for the entire time that this magazine has existed, given the Richard Mille parallels. To return to that lifeline bit we tossed off ever so casually, this relates to margins.

Ceramic and titanium boast exceptional virtues in the area of functionality, and are about as rare as dust. What is still unusual is the application of high polish, brushed finishing and other fine touches in these materials but, more prominently, the more pressing issue is one of production numbers.

Here, we encounter once more a certain lack of information but what numbers are available do not bode well for metals other than the precious sort and steel. On the other hand, optimists might see opportunity here for something other than hand-wringing.

Last year, Switzerland exported 8.4 million watches in steel but no data exists for titanium. Instead, the Swiss list watches in “Other Metals,” which excludes precious metals and combinations of a precious metal and something not precious, which are both separate categories.

In the Other Metals category of watches for 2024, only 1.2 million watches were made, representing roughly 14 percent of all watches exported in steel. This is not an improvement over previous years. Going back to 2016, 13.7 million watches in steel were exported versus 2.9 million watches in “Other Metals.” This represents 21 percent of all watches exported in steel.

This might be an odd variable to look at, or an odd way of comparing variables, but we will be looking at things in a more straightforward manner in the section on titanium. For now, it should be noted while we have total Swiss export figures from 2015 and even earlier, we only have data on the split of materials from 2016 onwards. That said, let us look at how many watches were exported in 2016, which was 25.4 million units.

Referencing our earlier figure for 2015, this already represents a downturn in volume. We select these years as they represent key milestones, with 2015 representing the first downturn for the industry since 2009 (by value, in CHF).

Value Propositions

In terms of volume, the 28.1 million watches exported represented a return to 2013 form. Since 2015, volumes have been trending down consistently, with exports last year amounting to just 15.3 million units. By value, Swiss exporters registered CHF 26 billion in 2024 versus CHF26.74 billion in 2023. Looking back to 2015, total value of watch exports was CHF21.5 billion; in terms of values, all figures are not normalized for inflation nor changes in the value of the Swiss franc.

This being said, the industry is clearly doing more with less, or making more with less, if you prefer. In short, we can reasonably conclude that volumes are down while values are up. We shall reach a little and suggest that this is what the Swiss watch industry would prefer, even if it says the opposite.

When you notice how the numbers shift in terms of the precious metals category (see the relevant subsection) over the years, there are implications on the “Other Materials,” category. This category includes everything that is not a metal of some kind, which includes everything from high-tech ceramic and sapphire crystals to plastics and composites. We are using this conclusion to support the idea that increasing revenue (i.e. value as we have been using it here) might be tied more to materials other than the precious stuff. In Tick Talk this issue, this writer even suggests that hard stone dials could support elevated prices that help improve the revenue for even steel models.

Why should we care about what watch brands earn? Well, for those of you who wonder, brands are gaining this value from us, the people who buy their lovely (hopefully) watches. They have to be convincing in their propositions – at least as much as the total design creations of Gerald Genta proved to be for Audemars Piguet and Patek Philippe.

While this is the gold standard, if you will pardon the pun, this should not be taken to mean some brand or other is going to burst out with transformative titanium or ceramic watch. None of the brands in the original Genta wave of the 1970s had smash hits right out of the gate. None of the brands that preceded them did either. Therefore, it seems likely that no brand ever will.

What about the example of Richard Mille then? The simplified answer is that the brand was not immediately successful. Arguably, many brands paved the way for Mr Mille when he launched his eponymous brand, back in the day. According to our industry sources (who, regretfully, must remain anonymous), even he did not have what might be called an overnight success. In fact, we are using Richard Mille as both an example and a counterpoint – the success of the brand is due to much more than material choices, and we trust that this is obvious. Thus, we use Richard Mille to steel man the proposition that brands will need more than wise material choices to secure their futures, or the future of their margins.

A Brighter Tomorrow

At this late stage of the introduction, we want to drag markets into this, just for a measure of completeness. If the United States finds itself an appetite for titanium watches, then the world will follow. UK specialist rag WatchPro estimates that a third of the US luxury watch market is taken up by just Rolex and if Rolex can sell more titanium sports watches there, it will naturally lean more heavily in this direction. Perhaps the brand will lean into this metal for the Land-Dweller; we propose a titanium and platinum version.

Read More: The Rolex Land-Dweller Turns Rumour to Revelation

This digression aside, we know the watch world wants more titanium and that Rolex enthusiasts in particular are keen to see more of this material in that brand’s offerings. This combination of brand, market and materials, as we propose, is what makes titanium exciting but, likewise, could also herald a bright future for technical ceramic.

On this note, Audemars Piguet promises that its Royal Oak ceramic cases are just as interestingly finished as the steel ones. The short of it is that watchmaking brands will want to bring traditional fine finishing and handwork to materials that do not typically receive these. If the material is one that requires overcoming technical hurdles, so much the better.

This leads directly to a final digression, which concerns opinions, again. We save these for both this introduction and our concluding thoughts, which is a pure opinion piece penned by the editor (also the author of this entire section). We decided on this format to avoid editorializing within bulk of the story, and the editor wants his say on specific examples that he cites. In this opinion piece, we will get back to matters such as the above example of Audemars Piguet, so do not expect more on this in the section on ceramic, for example. Further thoughts on subjects like that count as editorializing, in our view.

Technical Notes

Mechanical impedance: A measure of how much a structure resists when subjected to a force. Generally speaking, it relates forces with velocities acting on a mechanical system. The mechanical impedance of a point on a structure is the ratio of the force applied at a point to the resulting velocity at that point (source: sciencedirect.com). This metric combines with specific and tensile strength to give an indication of a given material’s toughness. Toughness is a measure that we find to be very useful in evaluating materials used in watchmaking.

Specific strength: A material’s strength (force per unit area at failure) divided by its density. It is also known as the strength-to-weight ratio or strength/weight ratio or strength-to-mass ratio. Specific strength is a critical property in material science; this metric allows engineers and scientists to evaluate the efficiency of any given material. Unlike absolute strength, which measures how much force a material can withstand, specific strength provides insight into how effective a material is relative to its mass. This makes it especially valuable in industries where reducing weight while maintaining strength is essential.

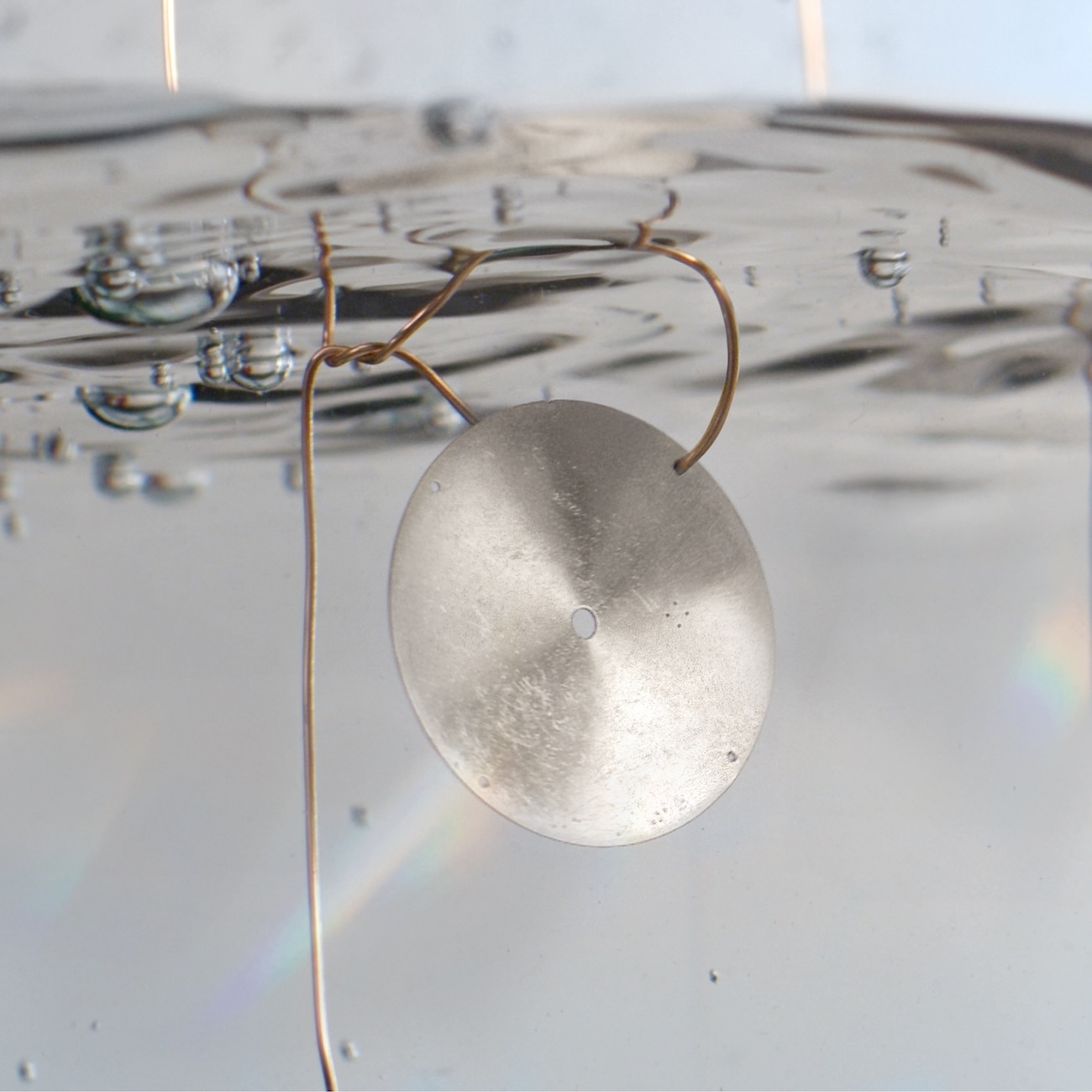

Passivation: This refurbished segment serves as a small correction to an unfortunate omission in this section originally, namely a definition so here is one: Passivation is a widely used chemical finishing process to remove contaminants and improve the corrosion resistance of metal parts, including stainless steel and alloys like Nitinol and titanium. As noted, this refers to a sort of treatment so it is quite apart from a property of any material. As an example, we continue with the still-relevant example of titanium although bronze and aluminium can be passivated too. Titanium is notable though for being only found in nature in oxide form.

Titanium readily reacts with oxygen at 1,200 °C in air, and at 610°C in pure oxygen, forming titanium dioxide. It is slow to reactwith water and air at ambient temperatures because it forms a passive oxide coating that protects the bulk metal from further oxidation. When it first forms, this protective layer is only 1–2 nm thick but continues to grow slowly; reaching a thickness of 25 nm in four years. (Material-Properties.org)

Ultimate tensile strength: the maximum on the engineering stress-strain curve. This corresponds to the maximum stress that can be sustained by a structure in tension. If this stress is applied and maintained, fracture will result. Often, this value is significantly more than the yield stress (as much as 50 to 60% more than the yield for some types of metals). The stress-strain curve contains no higher stress than the ultimate strength.

Even though deformations can continue to increase, the stress usually decreases after the ultimate strength has been achieved. It is an intensive property; therefore its value does not depend on the size of the test specimen. However, it is dependent on other factors, such as the preparation of the specimen, the presence or otherwise of surface defects, and the temperature of the test environment and material. Ultimate tensile strengths vary from 50 MPa for an aluminium to as high as 3000 MPa for very high-strength steels. (Material-Properties.org)

Hardness: In the watch trade, hardness is often defined in the same way for consumers as it is in jewellery – as the word hardness refers to gemstones. This usually means the Mohs scale, with some variations. This scale is fine for minerals, or things that have a mineral structure. Metals do not have such a structure, so the Mohs scale has to be modified to approximate the hardness of metals; it can also be argued that hardness is not an intrinsic property of metals so the relevance is a bit suspect.

Whatever test one uses though, we can roughly approximate the relative hardness of the metals so the Rockwell or Brinell scales give a rough indication but Vickers works just as well for our purposes.. For example, tungsten is one of the hardest metals, whether one goes by Vickers, Mohs, Rockwell or Brinell. This is useful because metals are not always commercially rated using the same scales, and there are many types of bronzes and titanium alloys in use, even just in watchmaking. On the other hand, the Mohs scale does well for ceramic because it is a mineraloid.

This story was first seen as part of the WOW #79 Summer 2025 Issue

For more on the latest in luxury watch reads, click here.

The post From Steel to Ceramic: How Material Mastery Shapes The Future of Luxury Watchmaking appeared first on LUXUO.