Fantasy or Reality: The Great Museum Escape

Museums have long been places of escape, where visitors step away from reality to explore the past — from treasured jewels to historical artefacts. Yet the very institutions built for escapism are now under intense spotlight, shaped by billion-dollar investments, private influence and renewed debates about ownership and cultural responsibility. Museums have traditionally been spaces of escape, but today they are more visibly shaped by the interests of those who curate their stories. Still, that influence has not erased the sense of wonder they continue to offer visitors.

Still, acknowledging these tensions does not erase the wonder these objects inspire. A gilded necklace, an ancient statue or a centuries-old tapestry can hold emotional and cultural weight that transcends ideology. Visitors can recognise the beauty and significance of what they see while also questioning how those pieces arrived there and whose stories they represent. Even as debates intensify around restitution, transparency and the ethics of collecting, the museum remains one of the few places where awe and accountability must coexist.

Museums: A Nation’s New Mega-Project

The global conversation around museums was recently reignited with Egypt’s massive investment into the nation’s new Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM). Lead-up events and the large-scale opening ceremony of the GEM are a prime example of how cultural projects have become part of strategic efforts to reclaim narrative authority, attract high-value tourism and position Egypt as a global centre for heritage and spectacle. The scale alone signals a shift where museums are no longer passive spaces but national assets with political and economic weight.

Egypt’s tourism economy is experiencing significant growth, with revenues reaching a record USD 14.4 billion in 2024. According to the World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC), Egypt’s tourism sector is vital to the country, contributing 3.7 percent to the GDP in FY 2024/2025 and creating millions of jobs. Egypt’s travel and tourism sector has surged past its pre-pandemic performance, supporting 2.7 million jobs in 2024 — surpassing its 2019 high. Momentum is expected to continue, with employment projected to reach 2.9 million in 2025 — a 22.3 percent increase from 2019 levels. WTTC President & CEO Julia Simpson noted that Egypt is witnessing a “strong revival,” with record economic output and sustained growth in visitor spending. She highlighted that the country’s cultural richness, expanding connectivity and strategic government investment in infrastructure and sustainable tourism are driving this upward trajectory and strengthening Egypt’s position as a global destination.

However, just days after GEM opened on 1 November 2025 — after more than two decades in the making — ticketing chaos erupted. On one day alone, over 27,000 tickets were sold — far exceeding the museum’s “safe” daily capacity of 20,000. Thousands of ticket buyers were reportedly turned away, with social-media outcry and complaints that many Egyptians cannot secure access. Some even appealed to MPs for intervention. A politician has publicly criticised the system, arguing that the current ticket allocation places Egyptian citizens in a “secondary category,” raising serious questions about whether the museum is truly accessible to the public it is meant to serve.

This raised a larger issue around how the museum’s ambition to be a world-class tourist draw may be at odds with local expectations when it comes to access and inclusion. This is followed by a decades-long delay in the construction timeline of the Grand Egyptian Museum, which also reflects a broader challenge like internal political upheaval, economic crises, pandemic disruption and now regional conflicts. However, it is arguably in these times that places of escapism like museums are needed the most. The GEM is a geopolitical and cultural statement — a dynamic power project launched at a time of volatility. Reported as one of the world’s largest archaeological facilities for a single civilisation, the GEM is a wonder in itself, housing over 100,000 ancient artefacts from the 30 dynasties of ancient Egypt over 500,000sq metres.

Even as Egypt pours billions into museum building and transforms its heritage into mega projects, these cultural milestones unfold against a backdrop of instability. However, the success of GED proves that these efforts can coexist with a nation navigating volatility and paradoxically, intensifies the awe surrounding the GEM’s ambition.

The New Cultural Power Brokers

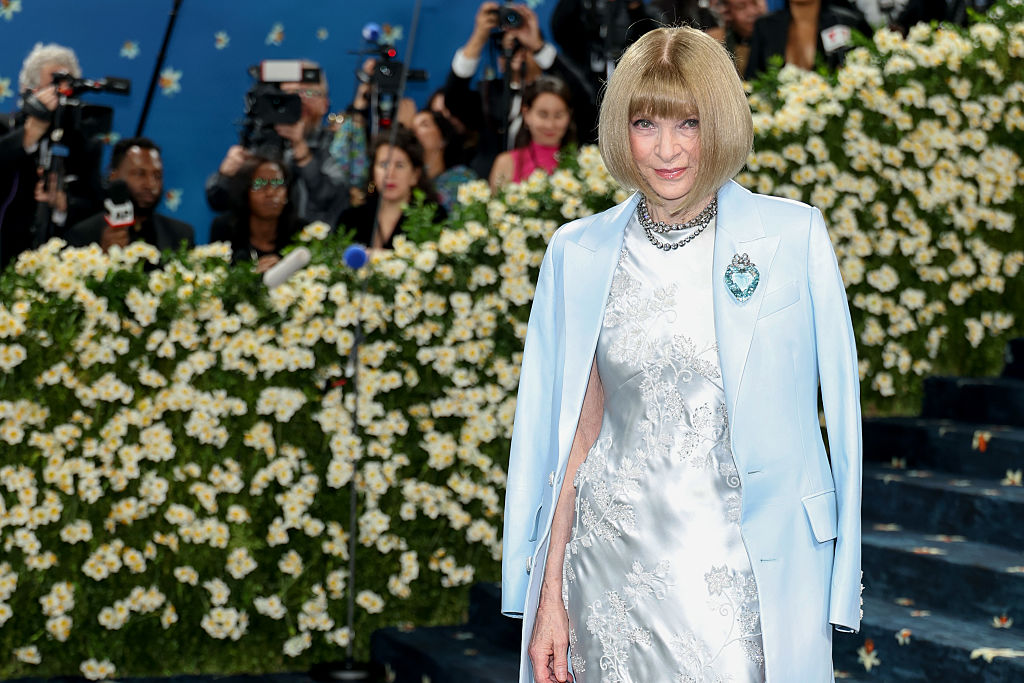

The 2026 theme of the MET Gala is “Costume Art” and Amazon founder Jeff Bezos and Lauren Sánchez’s funding of the event is more than a philanthropic gesture. It signals how private wealth will potentially determine the tone, direction and priorities of cultural institutions. In their new role, the couple will preside over everything from invites to logistics and overall presentation of the event. Anna Wintour publicly praised Sánchez as “a wonderful asset to the museum,” a quote that underscores how institutions are repositioning themselves around the influence of ultra-high-net-worth patrons.

The launch of “Costume Art” will be a milestone as it is the first exhibition to occupy the Met’s new Condé Nast Galleries. Curator Andrew Bolton describes it as transformative for fashion’s status within the art world, placing the dressed body at the centre of the museum’s storytelling. Yet when such landmark cultural moments hinge on billionaire funding, one can understand why it calls into question whose vision of culture is being elevated and who, ultimately, is the museum for? Their appointment breaks precedent as historically, legacy fashion houses have been the primary sponsors because they shape the event’s creative direction. A tech billionaire associated with fast fashion and global e-commerce feels misaligned with the Gala’s cultural DNA. In that same vein, Amazon’s association with fast fashion and exploitative labour stands in tension with the MET Gala’s focus on craftsmanship and artistry.

Yet there is also a pragmatic argument to be made. In an era where public funding for the arts is shrinking and museums face rising operational costs, large-scale private patronage has become essential for sustaining ambitious programming. Without patrons willing to underwrite entire wings or multi-year exhibitions, institutions like the MET could potentially struggle to build the kind of world-class experiences audiences now expect. One could argue that regardless of who signs the cheque, the preservation of art and the advancement of creative industries remain the ultimate beneficiaries.

There is also something to be said about how these strategic appointments of controversial figures contribute to the Met Gala’s ongoing relevance. After all, the event only became a true global phenomenon in the 1990s and early 2000s, when Anna Wintour took over as chair in 1995 and transformed it from a niche fundraiser into a celebrity-driven spectacle widely known as fashion’s Oscars.

Theft, Authenticity and the Question of Ownership

The recent Louvre heist has caused a ripple effect, triggering a wave of public scrutiny — revealing gaps in security and highlighting a larger issue of how museums acquire and authenticate their collections. On 19 October, four men used a stolen lift truck to access the Louvre’s Apollo Gallery, posing as workers with cones and high-visibility vests. Two climbed in the lift, forced open a window and broke into two display cases, grabbing nine pieces while brandishing angle grinders to ward off guards. The thieves made off with a collection of jewels carrying an estimated value of more than USD 100 million in what was described as a “stab at the heart of French history”. Among the items stolen were an emerald necklace set with more than 1,000 diamonds that Napoleon gifted to his second wife, Empress Marie-Louise of Austria, and a diamond and sapphire jewellery set worn by Queen Marie-Amélie and Queen Hortense.

This incident revived long-standing debates around colonial-era artefacts and transparency. For many institutions — especially in Europe — the spotlight has again turned to full disclosure. How did these objects arrive here and should they be returned? That being said — in a single incident — the Louvre robbery propelled France’s largely domestic crown jewels to international recognition, accomplishing a level of visibility no marketing effort could match. “Because of the drama, the scandal, the heist, the Apollo Gallery itself and the jewels that remain will likely receive a new spotlight and become celebrities, just like the Mona Lisa after 1911,” said Anya Firestone, a Paris art historian and Culture Ministry licensed heritage expert.

The British Museum and the Weight of Colonial Collections

The British Museum continues to face criticism for retaining artefacts from former colonies, so much so that it maintains a dedicated webpage on “contested objects from the collection.” Public scrutiny has intensified in recent years, not only over historically crucial pieces like the Parthenon Marbles and Benin Bronzes, but also in light of a major internal scandal in 2023 to 2024, when around 2,000 items — mostly jewellery, gems and gold mounts — were discovered missing, damaged or stolen from its storerooms, with some reportedly appearing for sale online. The scandal prompted staff resignations, heightened questions over security and reignited broader debates over restitution and repatriation, though legal constraints such as the British Museum Act 1963 make permanent returns extremely difficult.

In August 2023, the museum publicly acknowledged that up to 2,000 objects were missing or damaged, primarily from storage rather than public display. Many were valuable gold and gemstone items from Roman and Greek collections. Investigations revealed that some had been defaced or sold illegally. The museum responded by launching an internal investigation, terminating an employee and seeking public assistance. While hundreds of objects have since been recovered, some, such as melted-down gold mounts, are irretrievably lost.

This breach of security amplified criticism of the museum’s longstanding refusal to return contested artefacts to their countries of origin, a stance often justified on the grounds that other nations would struggle to protect them. MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy described this argument as “insulting,” noting that stolen items were nevertheless ending up on platforms like eBay. She has urged reform of the 1963 Act, which legally restricts the museum from permanently returning objects except in cases of duplication, damage or lack of public interest — a process that otherwise requires new legislation.

The controversy has also only accelerated global calls for restitution and highlighted the need for museums to reconcile with the imperial-era origins of their collections. The breach was also in direct contrast to the British Museum’s own claims that they are actively combating the global trade in looted antiquities, working with UK law enforcement and international partners to identify and return trafficked objects. Since 2009, it has claimed to have repatriated 2,345 items to Afghanistan, Iraq and Uzbekistan — including Buddhist sculptures damaged during the Taliban’s 2001 iconoclasm and later smuggled out of the country. These restored pieces are now on display in a new exhibition before being returned to the National Museum of Afghanistan.

In today’s highly culturally aware society, the lack of transparency around artefacts taken (or stolen) during Britain’s colonial era inevitably diminishes how visitors perceive what they are viewing. Withholding these pieces is also a lingering symbol of colonial power, especially when many of them are tied to religious or cultural traditions and therefore hold deeper significance in their countries of origin than they ever could behind a glass display halfway around the world from where they were taken.

In a bid to retain its position as one of the world’s greatest museums moving forward, The British Museum needs to balance public perception, historical preservation and the moral imperative to return objects that were acquired through exploitative means. These decisions will shape how generations understand the legacy of empire and the ethics of collecting, long after the initial draw o museum wonder and curated escapism fades.

Escapism Vs Accountability

Should visitors simply enjoy the fantasy of what they see without calling into question where they came from? Some argue that museums should remain spaces of wonder and escape, not courtrooms for historical grievances. They suggest that visitors should immerse themselves in the stories, beauty and fantasy that museums curate, without the burden of political context. Yet even this desire for escapism raises its own question of if museums can still offer pure fantasy when their foundations are increasingly under ethical examination. Those who buy a ticket should be able to both appreciate and question what they see before them and how it got there.

As an institution, the modern museum sits at a crossroads between fantasy, responsibility and cultural power. It is simultaneously a sanctuary, a tourist magnet, a political instrument and an ethical battleground. As travellers seek deeper experiences, and governments and billionaires reshape the cultural landscape, the museum escape is becoming more complex — and more revealing — than ever.

For more on the latest in culture and lifestyle reads, click here.

The post Fantasy or Reality: The Great Museum Escape appeared first on LUXUO.